Rushcliffe Design Code

Image by Ellastrated

Adopted 1 September 2025

Rushcliffe Design Code

Contents

- Planning and Design Process

- Street Hierarchy and Servicing

- Infill and Intensification

- Multi-dwellings and Taller Buildings

- Landscape

- Householder

- Rural

- High Streets and Retail

Appendix 2 - Glossary of terms

Appendix 3 - Area type geographies

Introduction

What is a design code?

The Rushcliffe Design Code Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) is an authority wide design code that sets design requirements regarding the expectations for design quality across the Borough of Rushcliffe. The design code has been created with local stakeholders, communities and their representatives to establish a vision for new development in their area. The aim of the design

code is to provide clarity through rules, which are supported by good practice design guidance, to allow applicants to bring forward

proposals with confidence.

Why do we need a design code

Design Codes are a requirement of the Levelling Up & Regeneration Act (LURA). The Act makes it a requirement for every local planning authority in England to prepare a design code for its area. The Rushcliffe Design Code supersedes the Rushcliffe Residential Design Guide Supplementary Planning Document. The Design Guide is therefore withdrawn from use.

What are benefits of a design code

The design code has been prepared to assist residents, architects, developers, builders and planning professionals when designing development proposals of all scales. The design code will be used by Rushcliffe Borough Council to set clear design expectations to support development proposals and aid the determination of planning applications.

The design code will also outline the process, considerations, qualities, and opportunities that will help to deliver high quality new development in Rushcliffe. The design code is not drafted as a substitution for design talent and does not intend to impose any particular tastes. The code is about promoting process and design rigour that lead to good design practice and proposals. In this way it aims to provide certainty in relation to design approaches likely to be deemed acceptable and consistency when determining design quality.

What the Design Code will and won’t do

A design code can be used to provide clarity on what is expected of applicants when submitting a design proposal, in some areas setting out the minimum requirements to achieve design quality. It may also set mandatory requirements and discretionary guidance.

It is relevant to all scales of development such as medium to large scale residential schemes, mixed-use developments and large regeneration sites across the Borough. Whilst parts of a code may also be important considerations for smaller sites, and homeowners wishing to extend their properties, and for other uses such as commercial development.

A design code cannot introduce new areas of planning policy, nor can it make new land allocations.

We acknowledge there are limitations to the code which are beyond its control and are managed through statutory or regulatory bodies. These include, but are not exclusive to:

- Energy: Energy conservation is currently established through Building Regulations set by central government using Approved Documents. Approved Document L: Conservation of fuel power sets minimum values for thermal transmittance (U-values), air permeability and efficiency of heating systems.

- Highways: The local highways authority is Nottinghamshire County Council who manage and set their own design standards.

Engagement Process - Summary

The findings were wide reaching (as to be expected given the wide geographic nature of the borough) but broadly consistent, with many common themes emerging between officers, elected members and the general public.

Overall, sustainability, better design quality and access to good quality open space was high on the agenda. Threading these together was a strong emphasis on active travel and movement to create more enjoyable places to walk and bike, as opposed to default to the car. Respondents highlighted the existing landscape and access to green space as key strengths. Alongside this was the unique architectural character and heritage of the existing settlements. However, participants highlighted car parking and the design of parking as a weakness that detracted from the enjoyment of new and existing communities. This was followed by high levels of traffic negatively impacting the quality of high streets, towns and villages, as well as being inhibitive to promoting active travel.

A more detailed summary of our findings can be found in the Baseline Appraisal.

Vision and Area Types

The consultant team alongside the council originally developed seven area types from their analysis of the wider borough. From this process, the team focused on urban form as the defining factor. Through a consultation process, this was simplified further down to five area types which define the broad geographical areas of Rushcliffe

In parallel, vision statements for each area type were developed and consulted upon to establish the focus of the code. The overall vision for Rushcliffe is:

'To secure well-designed, high-quality and sustainable development that reflects and enhances the local character of the Borough of Rushcliffe and supports vibrant and healthy communities.’

From this, the five area types and their visions are:

Urban (West Bridgford)

'To create new opportunities to live sustainably and increase the amenity for residents of the Borough’s principal urban area, including through improved connectivity.’

Riverside

‘To offer design approaches that find their distinction in the unique setting, challenges, and development pressures along the urban river front, by ensuring development respects and engages with the waterfront location, provides accessibility and connectivity to the riverside and connects with existing public rights of way, highways and cycleways.’

Key Settlements

'Integrate new development so that it belongs, captures the distinctiveness and best qualities of place, whilst adding something new and sought after.’

High Streets

'To promote vibrant high streets as places for investment and for people to spend time in, with a variety of reasons to visit. To ensure our high streets are safe, accessible and easy to visit, as well as being positive places to live in and around.’

Rural

'To keep villages as villages in scale and appearance, whilst adding new qualities to the local character. To maintain the agricultural character of the countryside and avoid urbanising ‘creep’ into rural and farming areas, including an appropriate and sensitive approach

to the conversion of rural buildings. Continue a tradition of conserving, restoring and enhancing the diversity of landscapes, historic

farmsteads, wildlife and the wealth of natural resources, ensuring it may be enjoyed by all.’

Site Specific Design Codes

Excluded from the authority wide Design Code are the following three sites:

- Strategic Allocation South of Clifton;

- Strategic Allocation East of Gamston/North of Tollerton; and

- Ratcliffe on Soar Power Station (land covered by the Local Development Order)

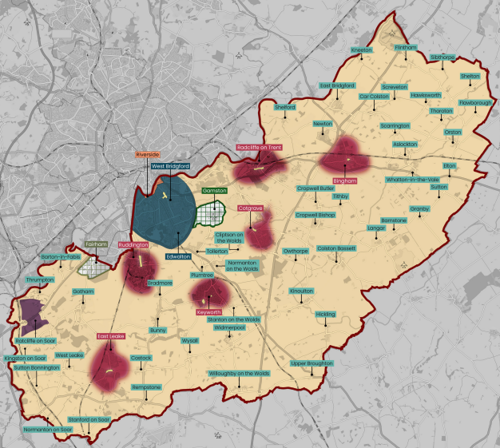

Key

Urban = dark blue

High streets = light green (within Bingham, Cotgrave, East Leake, Keyworth, Radcliffe on Trent, Ruddington and West Bridgford)

Riverside = orange

Key settlements = dark red

Fairham - Site Specific Design Code = light green hatched

Gamston - Site Specific Design Code = dark green hatched

Local Development Order (LDO) - Site Specific Design Code = purple

Rural = cream

A site specific design code has, or is being developed, for the two strategic allocations. These site specific design codes will be the only code applied to the strategic allocations. The site specific design codes contain a comprehensive development framework for the two strategic allocations, providing guidance for the preparation and determination of planning applications for the strategic allocations and to ensure the co-ordination of key infrastructure.

As part of the Local Development Order for the Ratcliffe on Soar Power Station, a site specific Design Guide was produced and approved. The Design Guide sets out the key design principles which applicants will need to demonstrate following as part of an application for a certificate of compliance under the Local Development Order. The Design Code will not apply to the Local Development Order for the Ratcliffe on Soar Power Station.

Area Type Geographies

The area covered by each of the area types are describe in more detail at Appendix 3.

If you are unsure which area type applies to your planning application, you should check with the Borough Council’s Planning and Growth team.

How to use the design code

The design code is a set of rules that describe what must or must not be included as part of a planning application. The design code is collated at Appendix 1 and as a downloadable table. Depending upon application type and scale, the table can be filtered to clearly set out which codes are relevant to your application.

Applicants are required to submit as part of a planning application a compliance statement to demonstrate their compliance or non-compliance with the design code. The submission of a compliance statement will form part of the validation requirements to register a planning application.

The codes are structured around eight key topics, each supported by a detailed ‘design note’. These are:

- 0. Planning and Design Processes

- 1. Street Hierarchy and Servicing

- 2. Infill and Intensification

- 3. Multi-dwelling and taller buildings

- 4. Landscape

- 5. Householder

- 6. Rural

- 7. High Streets and Retail

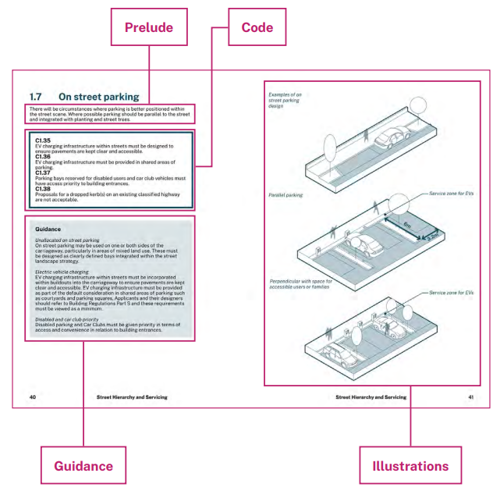

Each design note is divided into sub-topics. A typical page may include the following:

- A prelude: why is this subject important.

- Code: what are the rules – the musts and must nots.

- Guidance: promoting good design practice, they set out the should and should nots.

- Illustrations or case studies: demonstrating how to apply code or guidance and presenting examples of UK wide good practice. All visuals are indicative, offering an example of how the code or guidance might be implemented.

- Further supporting information: where topics are more complex or require situating, further detail is provided.

0. Planning and Design Process

When to apply this design note

Experience has shown that when applicants and their design teams follow a robust planning and design process design quality is understood at planning stages and can be upheld after permission has been granted.

Planning applications, including Section 73 applications, will not be recommended for approval unless they can demonstrate how they have followed the Planning and Design Process design note and meet the relevant requirements of the Design Code.

Proposals for major applications must be accompanied by a Design and Access Statement (DAS) that includes a detailed account of how the proposal has been developed following each of the nine stages of the Planning and Design Process design note.

Minor applications are not required to follow the Planning and Design Process design note but are advised to consult the document and use it as a best practice guide.

Purpose

To help speed up the planning process and improve the quality of design in Rushcliffe.

Following these nine stages will help applicants and their design teams to adopt good design principles and practices.

It outlines the planning and design process and considerations that will help to deliver high quality new development in Rushcliffe.

1. Context

During this first stage applicants should undertake research and fieldwork to develop their understanding of the role of the application site in its wider context through:

- Its history.

- Any cultural aspects, the importance of the place to local people and the social networks of the area.

- Its role as part of the economic landscape.

- Its role as part of the larger natural ecosystem and climate, and the wider Blue and Green Infrastructure network.

- The wider movement networks.

- Historic environment and the need to consider the significance of any heritage assets, including their setting.

Preparation

Understanding the context and setting

(RIBA 0 - 2)

- Context

- Stakeholders

- Benchmarking

- Site Appraisal

- Sustainable Baseline

Design Scheme

Applying the understanding gained to design a proposal

(RIBA 2 - 4)

- Concept Design

- Review

Planning Application

Building Regulations and Planning Conditions

(RIBA 4/5 +)

- Submission

- Additional Detail

2. Stakeholders

Applicants should identify who the relevant stakeholders are and plan how and when they will engage with them.

Local stakeholders may include residents, local businesses, not-for-profit organisations, schools, religious groups, other prominent

informal networks such as local heritage groups, sports clubs, parenting groups etc.

Authorities may include the Local Planning Authority (LPA), Parish Councils, Highway Authority, Utility providers, Emergency Services, Severn Trent Water, Internal Drainage Board, Environment Agency and other relevant organisations.

Applicants should decide whether to seek formal pre-application advice from the Local Planning Authority before moving forward to stage 3.

3. Benchmarking (design quality)

For residential proposals, applicants should use a tool to help appraise design quality and use this to form the basis of pre-application discussions with stakeholders.

It is recommended that applicants use Building for a Healthy Life (BHL). Where an applicant chooses not to use BHL they may use an alternative approach but should make the reasons for this explicit in the DAS and if unsure consult the LPA beforehand.

Building for a Healthy Life is recommended on the grounds it has been created to allow a broad range of people to use it easily – from members of a local community, local councillors, developers to local authorities – allowing those involved in a proposed new development to focus their thoughts, discussions and efforts on the things that matter most when creating good places to live.

Applicants should use BHL to think about the qualities of successful places and how these can be best applied to their proposed development in its wider context.

4. Site appraisal

The characteristics of a site will influence the layout and form of development. The response to those characteristics will significantly determine the distinctiveness of the design.

Site appraisals should be primarily map based using a number of topic-based ‘overlays’ where the appraisal is likely to be complex.

The analysis must include as a minimum, or justify where it does not include:

- Landscape and topography.

- Site micro-climate.

- Site ecology.

- Existing site conditions.

- Infrastructure.

- On and off-site movement network.

- On and off-site open space network.

- Opportunities and constraints.

- Heritage - above and below ground.

- Setting of a heritage asset where applicable.

- Green Belt.

Landscape and topography: the three-dimensional aspects of the site are likely to exert as much influence on the character of any

development proposal as its two-dimensional form.

Site micro-climate: watercourses, flood risk, drainage, gradients, exposure to wind, sun path, sunny slopes and shady slopes.

Site ecology: habitat and biodiversity characteristics of the site, designations and protections, mature trees, Tree Preservation Orders (TPO), hedgerow and ponds.

Existing site conditions: ground conditions, site boundaries, points of access, existing buildings and other structures on-site.

Infrastructure: utilities, nearby uses and facilities such as schools, heath care, shops etc.

On and off-site movement network: existing walking and cycling routes, public transport infrastructure, local street networks/hierarchies.

On and off-site open space network: green corridors, woodland, nature reserves, formal parks, squares, play areas, greens, sports fields etc.

Opportunities and constraints: summarising all the above positive factors in the area which gives the site an identity and character and identifying any negative aspects that development of the site could potentially improve.

5. Sustainable Baseline

The National Design Guide sets out an energy hierarchy for reducing the carbon cost of new buildings. It is based upon three principles:

- Reducing energy demand, both in construction and in use.

- Using energy-efficient systems within buildings.

- Maximising renewable energy sources, especially on-site generation, and community-led initiatives.

Applicants must complete the checklist in Appendix 1 of the Rushcliffe Low Carbon and Sustainable Design SPD and reference this in the DAS.

This stage will have implications for the proposed design as it may influence fabric-first decisions regarding building form, orientation, materials, procurement and on-site renewable energy sources.

Low carbon and sustainable design principles should influence design development from the outset.

Pre-determined site layouts and forms of development can rarely be retrofitted to achieve the same outcomes.

6. Concept design

Concept designs should be recorded on a map/plan, or a series of drawings and preferably supported by 3D illustrative sketches and annotations.

A concept design is not a detailed layout, but it must show the most important aspects of the proposed development such as the basic design decisions about the function, appearance, and layout of the proposed development.

Proposals of over 50 dwellings should provide a concept masterplan indicating delivery phases.

By stage 6 applicants should be able to answer the following questions:

- What will be the character of the development?

- How will the opportunities and constraints identified during the site appraisal be resolved?

- For residential development, how is the design approach responding positively to the 12 considerations of BHL?

- How is the design approach responding positively to input from the community and other stakeholders?

At this stage the applicant should also be able to answer questions about the intended approach to the following design considerations:

- What is the approach to accessing the development?

- What is the approach to prioritising walking and cycling?

- How will the development address the site boundaries and look out on adjacent land and development?

- How will the existing site ecology, structures or buildings influence the layout and form of the proposals?

- How will the development be given identity and be legible?

- What is the site wide approach to:

- Green and blue infrastructure

- Location and function of open spaces

- Sustainable drainage verges

- Tree planting

- Play spaces

- Allotments

- Foot/cycle-paths and cycle storage

- Bin storage and collection points

- Heritage assets and their setting

- How will biodiversity net gain be delivered within the site?

- What is the approach for reducing the carbon cost of the development?

- What is the approach to ensuring vehicle circulation and parking will not dominate the character of the development?

At this stage the applicant should summarise stages 1-6 with supporting plans, drawings and photographs and this information can be used in the DAS.

Applicants that choose to progress beyond stage 6 without seeking pre-application advice from the LPA are at greater risk of failing to comply with this Planning and Design Process design note and the Rushcliffe Design Code.

7. Design Review

Applicants and their design teams should now conduct a review of their design development thus far and discuss with the LPA whether a formal Design Review, using Design Midlands or another agreed forum, is appropriate.

Having conducted an appropriate review, applicants and their design teams should now produce a more developed proposal based on the analysis and evidence produced to date.

A draft DAS should accompany the developed design and explain the evolution of the proposal through stages 1 to 7 of the Planning and Design Process design note.

8. Submission

In addition to satisfying all validation requirements, Full and Reserved Matters applications are expected to submit as a minimum the following to ensure design quality can be accurately appraised and determined:

- Sections through the site and street elevations along the main frontage(s).

- Siteplans giving accurate location of trees, hedges, other landscape features, all other relevant structures, all adjacent buildings, bus stops and bus routes.

- Coloured and annotated elevational drawings providing details of all building materials and finishes.

- Drawings showing details of boundary design, lighting, and street path materials.

- 3D visuals.

- Labelling of LEAPS and LAPS (Local Equipped Areas of Play and Local Areas of Play).

9. Additional detail

Some details can be provided after the granting of planning permission and will be secured through planning conditions attached to the planning permission. This could include final specification, environmental issues, circular economy, end-of-life disposal, or arrangements during construction such as phasing.

C0.1

Proposals for major applications must be accompanied by a Design and Access Statement that includes a detailed account of how the proposal has been developed following each of the nine stages of the Planning and Design Process design note.

Masterplanning

Producing a masterplan for a site can be an effective way of creating a successful development and navigating the planning and design process. This is because the masterplanning process can help to clarify policy and design expectations, set a clear vision for a site, inform infrastructure decisions and viability assessments, and identify requirements for developer contributions early in the planning

process.

What is a masterplan?

A masterplan sets the vision and implementation strategy for a site focusing on site-specific proposals such as landscaping, layout and mix of uses, transport and movement, scale, massing and grain of development. A masterplan is often accompanied by a range of supporting evidence such as a local character study or landscape assessment. If a development is to be delivered in several phases, an implementation strategy should also be included.

Masterplans and Design Codes

Any masterplan being prepared for a site within Rushcliffe is expected to demonstrate how the mandatory requirements and further guidance within the Rushcliffe Design Code can be implemented through the site-wide design proposal. In some cases, it may also be necessary to set out how more detailed design requirements are being met in a separate site-specific design code which can accompany or follow the overall Masterplan.

Masterplans for development sites can be produced by the landowner/ developer on their own, or in partnership with the local planning authority. In all instances the masterplanning process should be collaborative and multidisciplinary and subject to a separate community and stakeholder engagement exercise so that site opportunities and constraints are understood early on.

Care should be taken to ensure that masterplans are viable and understood by all stakeholders and include accurate representations of what the proposed development will look like. They must not be misleading to the public.

The level of detail included in a masterplan may vary depending on the complexity of the site. The National Model Design Code section 2.c Masterplanning includes guidance on what a notional masterplan is likely to include.

1. Street Hierarchy and Servicing

When to apply this design note

This design note is required to be followed when a development proposes the creation of a new street or multiple new streets.

The term ‘street’ will be applied at the discretion of the LPA to all routes providing access, vehicular or otherwise, that connects to, through and out of new residential and mixed-use development.

All new development involving the creation of a single or multiple new streets must apply the Rushcliffe Street Hierarchy. This hierarchy includes three street types, each with varying spatial characteristics that reflect their role and function in the hierarchy.

Pre-application

It is recommended during the pre-application stages that applicants discuss and agree in writing with both the LPA and Highways Authority a proposed street hierarchy indicating street types for each new street being proposed.

This requirement covers all proposals ranging from the creation of a single street to a network of multiple new streets. The overall design of each proposed street must conform to the design parameters for the corresponding street type, set out at 1.2 Tertiary Streets, 1.3 Secondary Streets and 1.4 Main Streets of this design note.

It is anticipated that not all proposals will contain each street type.

The Rushcliffe Street Hierarchy has been designed in consultation with Nottinghamshire County Council Highways Authority. Applicants must engage early with Nottinghamshire County Council and Borough Council Officers to explore adoptable street designs and any proposed variations from the Nottinghamshire County Council Highway Design Guide, which all applicants should refer to when proposing the creation of new streets.

Rushcliffe Borough Council require applicants and their designers to agree the general geometry of residential streets in consultation with the Highway Authority.

This design note follows the principles and guidance in Streets For A Healthy Life and applicants and their designers should consider this and other relevant design guidance including Manual for Streets I and II and Building for a Healthy Life.

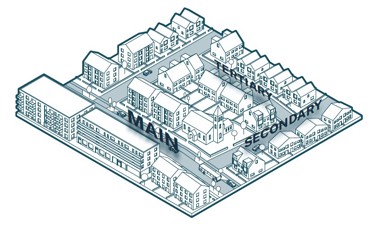

1.1 Street hierarchies

C1.1

The spatial characteristics of different street types must be distinctive from one another.

C1.2

Streets proposed as part of new development must be designed with traffic-calming measures.

Guidance

When considering the character of a new development it is common to consider creating a range of different house types, scales, materials and densities. But it is equally important to create a sense of character through a variety of streets and spaces. The spatial characteristics of different street types must be distinctive from one another. Distinction can be in the form of enclosure ratio, carriageway width, land use, landscaping, and parking.

Streets proposed as part of a new development should be designed for vehicles speeds of 20mph or lower and should be designed to give pedestrians priority over vehicle users.

A hierarchy comprises a network of streets and spaces progressing from the entry (or entries) to the development site progressing down to the most minor streets and courtyards.

Rushcliffe Street Hierarchy

Tertiary: Quietest residential streets with lower levels of traffic. Often Homezone principles apply.

Secondary: The most common residential street. Non-residential uses can be present.

Main: Entry (or entries) to a development. Main public transport, vehicular and cycle routes

The Rushcliffe Street Hierarchy is intentionally inverted to put the emphasis on the requirement to create streets that give people priority over vehicles, and which are safe and attractive to all users.

1.2 Tertiary streets

These quieter streets are designed for people first and are not normally bus routes. A tertiary street can have clear, designated footpaths or can be designed to Homezone principles with a level surface. Cyclists will share the main street surface with vehicles.

Traditionally this street type might include Mews, Courts, Yards, Lanes, Closes and Cul-de-sacs. Tertiary Streets are quieter residential streets. They can be connected at both ends of the street, or provide no through routes for vehicles (e.g. cul-de-sac).

C1.3

Street lighting must be present on all new tertiary streets.

C1.4

New tertiary streets must have at least one pedestrian priority feature to help encourage slower traffic speeds every 40 metres, or at least one feature where a street is less than 40 metres in length.

C1.5

On-street parking on tertiary streets must be designed as clearly defined parallel and/or chevron bays that are integrated within the street landscape strategy.

C1.6

Verges and planting areas that contain street trees must be at least 2 metres wide on tertiary streets.

Guidance

Enclosure ratio

Buildings are usually situated on both sides of tertiary streets giving a strong sense of enclosure to create a residential character and positive pedestrian and cycling environment. In some contexts a tertiary street can feel comfortable where the width of the space is less than the height of the buildings on either side.

Setbacks

Buildings may be set back by between 0.5 and 3 metres to provide a threshold or front garden. This may also accommodate a bin store, cycle store and a low boundary wall, railing or fence.

Space for walking and wheeling

Tertiary streets may have a level surface, but this does not preclude footpaths. Surface materials should be suitable for use by disabled people, avoiding patterns that may create visual confusion and potential hazards for visually impaired users.

Cycling on the carriageway will normally be acceptable – see LTN 1/20 for further guidance.

Pedestrian priority interventions

Tertiary street design must incorporate traffic calming features to encourage slower traffic speeds. These features reinforce pedestrian priority by intentionally forcing vehicles and cyclists to slow down to walking speeds and/or come to a halt.

Vehicle speed

Tertiary streets should be designed for 20 mph or less, or 15 mph for shared surfaces.

In curtilage parking

Vehicular access to plots is permitted from a tertiary street, but parking to the front of the building line is discouraged and should not dominate streets.

On street parking

Can be provided, but not allocated. It is recommended that provision is made for one parking space per three dwellings.

Parking proposed on either side of a street should be staggered and not directly opposite.

Service strips

To be a minimum width of 1 metre and should not read as a narrow footway.

Tertiary street design will not be permitted where:

- A lack of space to park vehicles is likely to result in pavement parking.

- The street is not part of a connected network for walking and cycling.

- ‘Segregation sandwiching’ occurs.

- There is a lack of differentiation between the surface of the street and the adjacent on street parking bays.

- Planting strips are too narrow and will be difficult to maintain.

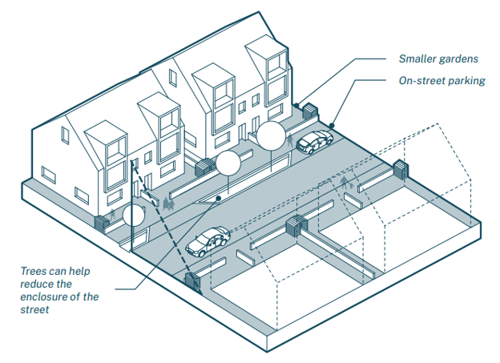

residents and pedestrians in tertiary streets and secondary streets in

urban contexts.

- On-street parking

- Smaller gardens

- Trees can help reduce the enclosure of the street

play and linear park (Photograph by Rebecca Clark)

speeds. Varied planting creates a buffer between houses

and street, whilst clear visibility of entrances and front

windows help animate the street.

(Photograph by Rob Beardsworth)

different takes on the conventional residential street.

Building line gives continuity and a strong sense of

enclosure. Pedestrian priority intervention using a planting

area that intentionally narrows the street to disrupt

vehicle continuity. An example of how 3-storey house

types can enable a wider street section compromising the

sense of enclosure. Here the additional street width allows

for the relatively deep liner park alongside the vehicle

path and footpath. Note pedestrians feel safe and

comfortable to walk in the vehicle path.

(Photographs by Rebecca Clark)

1.3 Secondary streets

The most common form of residential street. Secondary streets usually provide a link between main streets and form a network to tertiary streets and spaces.

Designed for 20 mph or less, secondary streets are people-orientated residential streets much like their tertiary street counterparts. They differ in that some non-residential uses such as cafes, community and retail space may be present and traffic volumes are slightly higher. They can also be good secondary locations for larger community facilities such as schools and health centres.

These streets typically have a clear distinction between vehicular and pedestrian space, with defined kerbs and footways. Secondary streets are not usually bus routes and cycling in the carriageway will normally be acceptable.

C1.7

Street lighting must be present on all new secondary streets.

C1.8

On secondary streets, pedestrian crossovers located across the mouth of side street junctions must maintain the trajectory of the footpath (desire lines).

C1.9

New secondary streets must have at least one pedestrian priority feature to help encourage slower traffic speeds every 50 metres, or

at least one feature where a street is less than 50 metres in length.

C1.10

Level footways must be maintained across driveway access points on secondary streets.

C1.11

On-street parking on secondary streets must be integrated within the street landscape strategy.

C1.12

New secondary streets must integrate areas of soft landscaping, including SuDS and tree planting, into the design of the street.

C1.13

Verges and planting areas that contain street trees must be at least 2 metres wide on secondary streets.

Bicycles and vehicles share the carriageway. Absence of frontage parking creates a sense of enclosure which will strengthen as street trees mature. Verges on both sides are designed as SuDS and segregate footpaths. Street lighting and lack of crossovers onto driveways add to a safe and convenient pedestrian environment.

Other features of interest include the use of timber posts to prevent parking on the verge (always consult Highways Authority as such features could be deemed as a maintenance issue).

Tree lined verges on one side of the street creates secondary enclosure and parallel parking bays on the other side of the street help maintain the sense of enclosure (perpendicular bays would increase street width). Bays are interspersed with street trees to break up the visual dominance of parked cars.

Other features of note include how street lighting and lack of crossovers onto driveways add to a safe and convenient pedestrian environment.

Guidance

Enclosure ratio

Can vary according to the adjacent land uses and local context. In an urban area secondary streets can feel comfortable where the width of the street is only a little wider than the height of the buildings. In suburban settings the width of the street can be at least twice that of the building height, allowing more space for conventional footpaths, verges, street trees and on street parking.

Setbacks

Buildings may be set back by between 0.5 and 6 metres to provide a threshold or front garden. This may also accommodate a bin store, cycle store, a low boundary wall, railing or fence. Principal elevations and front doors should face the street with frontage access for all buildings.

Space for walking and wheeling

In most cases, secondary streets will have at least 2 metre wide footpaths on both sides of the carriageway, that are unobstructed for pedestrians. Pedestrian crossovers with dropped kerbs located across the mouth of side street junctions must maintain the trajectory of the footpath (desire lines) and not deviate further down the side street.

Cycling on the carriageway will normally be acceptable – see LTN 1/20 for further guidance. Street lighting must be present.

Pedestrian priority interventions

Secondary street design must incorporate traffic calming features to encourage slower traffic speeds. These features reinforce pedestrian priority by intentionally forcing vehicles and cyclists to slow down to walking speeds and/or come to a halt.

Vehicle speed

Secondary streets should be designed for 20 mph or less.

In curtilage parking

Where curtilage parking is provided at the front of dwellings level footways must be maintained across driveway access points.

On street parking

Can be provided, but not allocated, on one or both sides of the carriageway. It is recommended that provision is made for one parking space per three dwellings. In streets of mixed land use a higher ratio may be acceptable by agreement.

On street parking must be designed as clearly defined bays integrated within the street landscape strategy.

Service strips

To be a minimum width of 1.5 metres and should not read as a narrow footway.

Secondary street design will not be permitted where:

- A lack of space to park vehicles is likely to result in footway parking.

- Tandem parking is proposed.

- Street is not part of a connected network for walking and cycling.

- ‘Segregation sandwiching’ occurs.

- Lack of differentiation between the surface of the street and adjacent on street parking bays.

- SuDS are absent.

- Planting strips are too narrow and will be difficult to maintain.

- Footways undulate due to multiple driveway access points.

- Backs or sides of properties on to street create a deadening effect to the street.

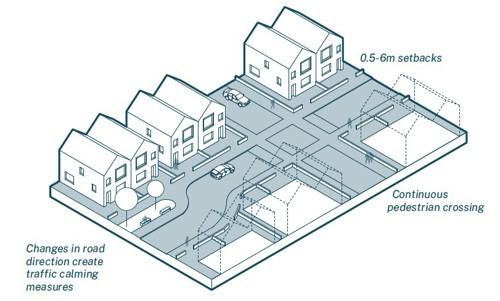

Illustrative secondary street designed for low speeds incorporating examples pedestrian priority measures.

- Changes in road direction create traffic calming measures

- 0.5 - 0.6 metre setbacks

- Continuous pedestrian crossing

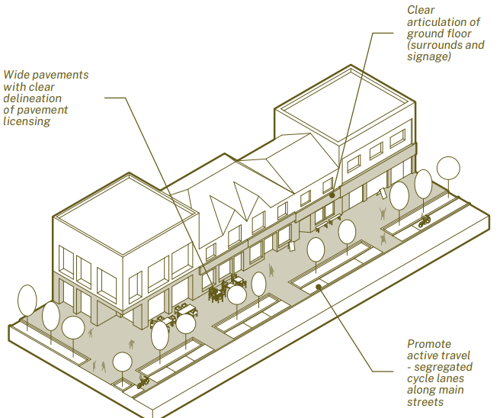

1.4 Main streets

Sometimes also referred to as primary streets, main streets are the strategic routes for vehicular traffic through a development but must also be designed to balance this function with the needs and safety of all users. Not all new developments are required to contain a main street.

C1.14

Main streets must be designed with a clear distinction between vehicular, cycle and pedestrian space.

C1.15

Protected space for cycling must be provided on all new main streets.

C1.16

A main street must not solely provide access to residential uses.

C1.17

Main streets must be designed to accommodate public transport.

C1.18

Street lighting must be present on all new main streets.

C1.19

Pedestrian crossovers with dropped kerbs located across the mouth of side street junctions must maintain the trajectory of the footpath (desire lines) on all new main streets.

C1.20

New main streets must have at least one pedestrian priority feature to help encourage slower traffic speeds every 60 metres.

C1.21

Level footways must be maintained across driveway access points on new main streets.

C1.22

On-street parking on main streets must be designed as clearly defined parallel and/or chevron bays integrated within the street landscape strategy.

C1.23

New main streets must integrate areas of soft landscaping, including SuDS and tree planting, into the design of the street.

C1.24

Verges and planting areas that contain street trees must be at least 2 metres wide on main streets.

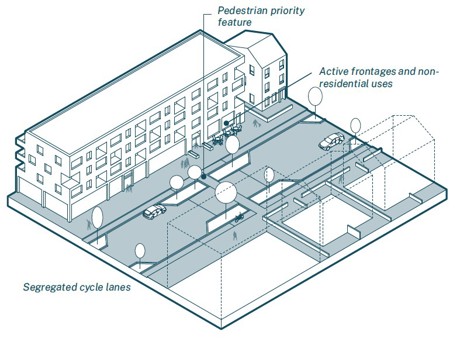

- Active frontages and nonresidential uses

- Pedestrian priority feature

- Segregated cycle lanes

Guidance

Main Streets

Main streets must be designed with a clear distinction between vehicular, cycle and pedestrian space and can vary in their design according to the specific context and function.

Protected space for cycling must be provided – see LTN 1/20 for further guidance.

A main street must provide direct access to a mix of land uses. Where it is only providing access to residential development the street must be designed as either a secondary or tertiary.

A main street must provide direct access to a mix of land uses. Where it is only providing access to residential development the street must be designed as either a secondary or tertiary.

A main street can vary in character along its length according to the adjacent land uses and townscape character. An important design distinction to make is that a main street is not a character area itself. A main street will pass through different character areas, or

neighbourhoods, and will take on the characteristics of that locality.

The National Model Design Code stipulates that main streets may vary and take on the character of an avenue, boulevard or parkway, especially in larger schemes.

Parkways

Streets with a wide central natural grass reservation with trees, along with carriageways and pavements. These can be suitable for new suburban development in Rushcliffe.

Boulevards

Streets with a central carriageway with secondary one-way streets for access and parking with trees planted in the reservations. Less appropriate for certain area types in Rushcliffe.

Avenues

Streets with a central carriageway and wide tree-lined verges either side. Can be suitable for both urban and suburban settings within Rushcliffe.

Public transport

Main streets must be designed to accommodate public transport, allowing for the integration of bus stops, even if no bus service is planned in the short term.

Space for walking and wheeling

Main streets should have footways that are at least 2 metres wide on both sides of the street, that are unobstructed for pedestrians, and include crossings where necessary. Street furniture should be provided as land uses dictate.

Pedestrian priority interventions

Main streets will tend to have straighter alignments, and therefore designers must use pedestrian priority features to help encourage slower traffic speeds at least every 60 metres. These features must reinforce pedestrian priority by intentionally forcing vehicles and cyclists to slow down to walking speeds and/or come to a halt.

Vehicle speed

Main streets should be designed for 20 mph or less.

In curtilage parking

Where curtilage parking is provided at the front of dwellings level footways must be maintained across driveway access points.

On street parking

Defined car parking bays may be used on one or both sides of the carriageway that are integrated within the street landscape strategy.

Service Strips

To be a minimum width of 2 metres and should not read as a narrow footway.

Landscaping

Street trees and SuDS are an important feature and must be present and integrated within main streets.

Main (primary) street design will not be permitted where:

- There is insufficient protected cycle infrastructure.

- A lack of space to park vehicles is likely to result in parking on footpaths.

- Lack of differentiation between the surface of the street and adjacent on street parking bays.

- SuDS are absent.

- Planting strips are too narrow and will be difficult to maintain.

- Footways undulate due to multiple driveway access points.

- Backs or sides of properties on to street create a deadening effect to the street.

1.5 Designated parking

As car ownership continues to increase, parking is now a significant design issue across Rushcliffe. It can be an emotive issue leading to disputes between neighbours, missed bin collections and a contentious design issue leading to planning refusals.

Parking needs to be designed carefully, and parking capacity needs to be flexible. What works on one site, may not work on another. Where and how vehicles are parked has a massive impact on how a place looks, feels and functions. There needs to be a balance between achieving sufficient parking without it being over-dominant and detrimental to other aspects of good design

C1.25

In-curtilage parking located in front of the main building line must be integrated with an area of soft landscape that is equal to or greater than the size of the parking area.

C1.26

All parking spaces must have permeable surfaces or be connected to a sustainable urban drainage system.

C1.27

Carports must be offset by 1 metre from the highway and garages must be offset by 5.5 metres from the highway and be of sufficient dimensions to allow for the primary purpose of parking a vehicle.

Guidance

Parking principles

Tandem parking arrangements result in displaced car parking which leads to the obstruction of highways and prevent refuse collections. Where space is left in curtilage outside homes for the possibility of tandem parking, the highways authority will not usually count the additional parking space towards agreed parking provision.

In curtilage parking

Parking within the curtilage of properties is generally better located at the side of the house or partially behind the building line as opposed to entirely to the front. Tandem parking will generally not be counted as two spaces.

Where parking is located at the front of a property it must be integrated with soft landscaping, preferably equal to or greater than the size of the parking area. Landscaping should be arranged in such a way that it is not easily converted into another parking space.

1.6 Shared parking areas

A move towards collective parking strategies will allow for streets that are not dominated by parked vehicles and maximise opportunities for soft landscaping and amenity spaces which bring social and environmental benefits and may also allow for more efficient land uses.

C1.28

Access to rear parking courtyards must have headroom for resident owned trade vehicles to enter.

C1.29

Proposals for private drives must demonstrate why an adopted tertiary street cannot be used instead.

C1.30

Private drives must not serve more than 5 dwellings.

C1.31

All private drives must have an entry point via a crossover maintaining pedestrian and cycle priority and have a dwelling terminating the view in.

C1.32

In parking squares, bays must be arranged in clusters of up to 5 and integrated with areas of soft landscaping.

C1.33

Rear parking courtyards must be directly overlooked by homes, with street lighting present.

C1.34

Neighbourhood-scale parking squares must be enclosed by local facilities on at least three sides (exceptions may be deemed acceptable – see guidance note).

Guidance

Rear courtyards

To be used sparingly. Poorly designed rear parking courtyards are often under-used by residents, leading to displaced parking in streets. Rear parking courtyards should be small in scale and must be directly overlooked by homes, with street lighting present. In rear spaces, parking bays should be arranged in clusters of 4 or 5 and should be integrated with areas of soft landscaping and tree planting.

Within rear courtyards homezone principles will help pedestrians take precedence over vehicle movements. Surface materials in courtyards should vary from the surface material used for the carriageway. Access to rear parking courtyards must have headroom for resident owned trade vehicles to enter to prevent displaced parking of larger vehicles.

lighting and well-detailed private parking courtyard with bays arranged

in clusters of three.

(Photograph by Rob Beardsworth).

Shared private drives

Applicants and their designers must justify every private drive being proposed to the LPA and Highway Authority and demonstrate why an adopted tertiary street cannot be used instead. Dead-end shared drives should have a shared surface and turning areas so that all vehicles, including delivery vehicles, can egress in forward gear.

Parking squares

Also known as front courtyards. These are areas devoted to residential parking, allocated or not, enclosed by surrounding houses. Parking squares can provide additional spaces for other nearby houses and visitors. The optimum number of spaces will depend on the layout, types and density of housing proposed, but could be based on the number of homes within a 50 metre radius of the square with additional spaces for visitors and deliveries. Parking squares should also provide secure cycle parking and some seating is recommended.

Neighbourhood parking squares

Suitable only in larger developments. Neighbourhood-scale parking squares must be enclosed by local facilities on at least three sides. Exceptions to this may be where a parking square is associated with public open space or outdoor facilities in which case less enclosure may be deemed acceptable.

Car parking provision is intended for users of the facilities such as shops, childcare, health and other community uses. The optimum number of spaces would depend on land uses but is likely to be between 30 and 50 spaces.

Bin collection

As refuse vehicles are only able to access adopted highways, suitable bin collection points should be provided for any dwellings served by private drives with collection points adjacent to the public highway. The expectation will be for residents to place their bins at such collection points prior to collection and remove bins after emptying.

Servicing

It is important to ensure streets and public spaces are designed with management and maintenance in mind (this is dealt with further at Section 4.7 of the Landscape Design Note). Even a well-designed space will end up having a negative impact on the environment and local community if it is not appropriately maintained in a discreet and proportionate manner

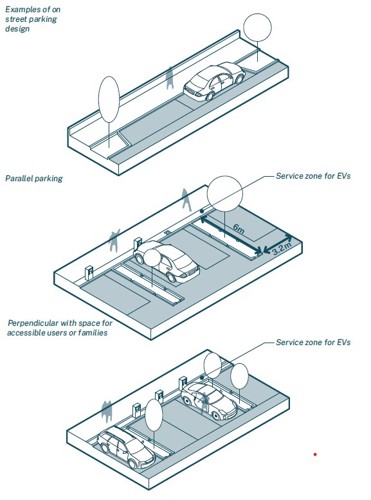

1.7 On street parking

There will be circumstances where parking is better positioned within the street scene. Where possible parking should be parallel to the street and integrated with planting and street trees.

C1.35

All agreed provision of EV charging infrastructure within streets must be designed to ensure pavements are kept clear and accessible.

C1.36

EV charging infrastructure must be provided in shared areas of parking. Level of provision to be agreed with Local Planning Authority and Local Highways Authority.

C1.37

Parking bays reserved for disabled users and car club vehicles must have access priority to building entrances.

Guidance

Unallocated on street parking

On street parking may be used on one or both sides of the carriageway, particularly in areas of mixed land use. On street parking must be designed as clearly defined bays integrated within the street landscape strategy.

Electric vehicle charging

EV charging infrastructure within streets must be incorporated within buildouts into the carriageway to ensure pavements are kept clear and accessible. EV charging infrastructure must be the default consideration in shared areas of parking such as courtyards and parking squares. Applicants and their designers should refer to Building Regulations Part S and these requirements must be viewed as a minimum.

Disabled and car club priority

Disabled parking and Car Clubs must be given priority in terms of access and convenience in relation to building entrances.

1.8 Cycle storage

New developments should make it more attractive for people to choose to walk or cycle for short trips helping to improve levels of physical activity, and reduce the impact of car use on air quality and local congestion.

C1.38

All new dwellings must be purposely designed with an adequately sized and secure space for the storage of at least one adult sized

bicycle.

Guidance

Communal storage

A common solution for groups of smaller properties or apartment buildings is to provide communal cycle parking facilities for residents only. These should be secure and located on the ground floor. Outdoor cycle storage should be weather-proof and located in well-overlooked and well-lit locations. Cycle storage solutions must take account of the need for at least a 2 metre circulation space. Stacked storage may provide a solution.

Visitor cycle storage

Publicly accessible cycle parking for visitors is needed in convenient locations close to the entrances to homes, shops and other facilities. It should also be included in all publicly accessible shared parking areas such as residential and neighbourhood parking squares. Whilst visitor cycle storage may differ from that provided for residents, it must always provide sited and secure undercover cycle parking, with overlooked facilities that are positioned close to entrances to buildings.

Location

Cycle storage should be easily accessible and located close to entrances to make the choice to cycle convenient and desirable to move around the neighbourhood or access local services.

Biodiversity

On-street cycle storage is a great opportunity to enhance biodiversity through green roofs or insect habitats.

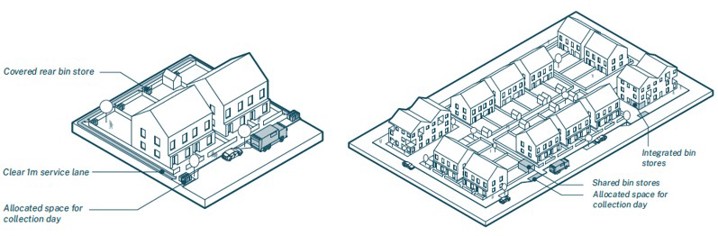

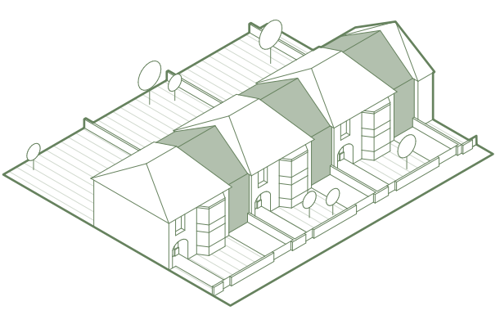

1.9 Recycling and waste storage

Most properties in Rushcliffe now have at least three wheelie bins. Often the most convenient and practical storage point is at the front of properties but it is important to avoid bins being left out in haphazard and unsightly ways. Convenient and practical storage solutions need to be integrated sensitively and screened from view. Other design considerations should enable the flow of air and avoid building entrances becoming cluttered.

C1.39

Proposals for new properties or use of land must clearly set out waste collection strategies.

C1.40

Bin storage must be enclosed to provide a positive outlook for residents and designed to be robust, secure and ventilated.

Guidance

Proposals for new properties or use of land must clearly set out waste collection strategies. Sometimes a combination of different strategies may be appropriate across larger sites and different housing type and tenure groups. For example, whilst housing in rural and suburban areas may be expected to accommodate bin storage and collection solutions on plot, apartments and medium-density housing in urban areas may suit collective, not individual, strategies

Bin storage solutions must be enclosed to provide a positive outlook for residents and designed to be robust, secure and ventilated. Applicants and their designers should also consider fire compartmentalisation, cleaning and maintenance, and efficiency through internal rotation of bins via a management strategy.

Designing bins stores to share an architectural style with the main buildings on a site will maintain the quality of the development. Off-the-shelf retrofitted solutions are often visually intrusive, inconvenient or have a short design life.

Biodiversity

Communal bin stores should integrate green roofs and insect habitats to support biodiversity.

Left - Individual

- Covered rear bin store

- Clear 1 metre service lane

- Allocation space for collection day

Right - Collective

- Integrated bin stores

- Shared bin stores

- Allocated space for collection day

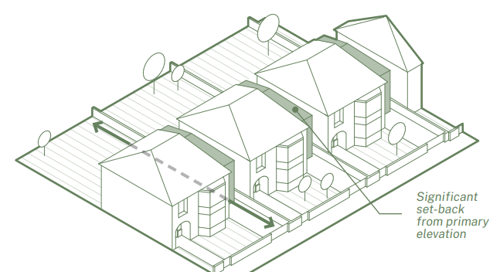

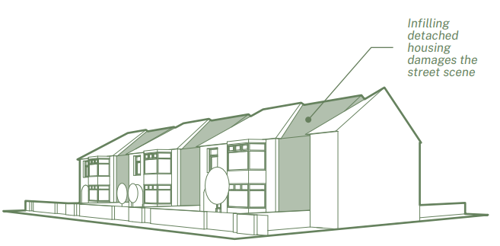

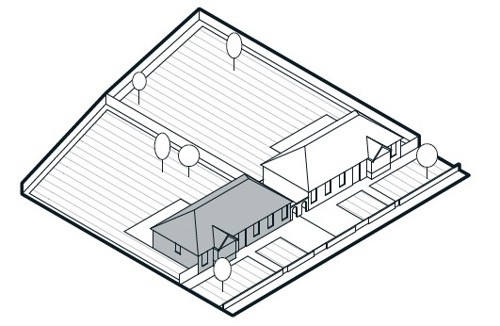

2. Infill and Intensification

When to apply this design note

Infill and intensification development takes place within an existing built-up area. It can be on a small-scale such as the development of a gap site within an existing street frontage, or on a larger scale. For example where a proposed change of land use or demolition(s) results in new development opportunities.

This type of development is usually on brownfield land (previously developed land) and usually viewed positively due to being inherently more sustainable than expansion into greenfield sites.

The priority when designing for infill and intensification is to be a good neighbour to surrounding buildings and uses.

2.1 Area type (local character)

The NPPF, National Design Guide and Rushcliffe Borough Local Plan requires new development to respond to the distinctiveness and character of the existing built and natural environment.

C2.1

Proposals must have regard to:

- The relevant Area Type vision, and

- Area Type worksheets in the design code Baseline Appraisal taking into account development pattern of the local area ,such as building lines, plot structure and grain.

Guidance

The scale, proportions and grain of new development should make efficient use of the land available, whilst having regard to surrounding development and the Area Type visions. As infill and intensification occurs the overall scale of development should be appropriate to each area type. For example, urban forms of development will be inappropriate in rural or village settings and suburban forms of development will be inappropriate in compact urban areas of West Bridgford and Trent Riverside.

Successful design approaches rarely copy what’s already there but rather take inspiration from it. Applicants and their designers are encouraged to observe, absorb, and reinterpret local context and character by analysing the local vernacular of a site. Understanding what local features are of importance to the local character and using this understanding to inform the design of new development.

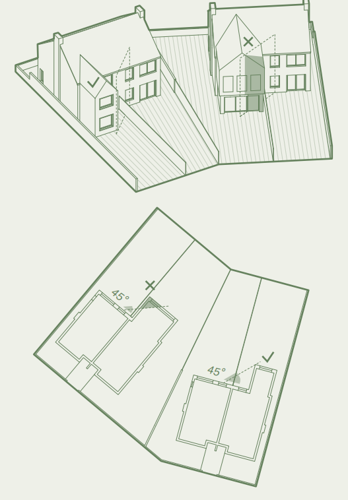

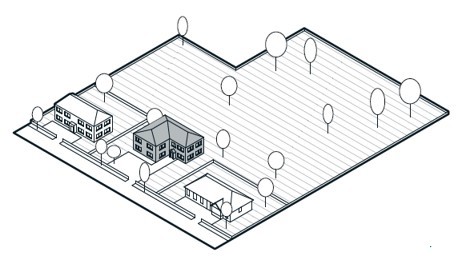

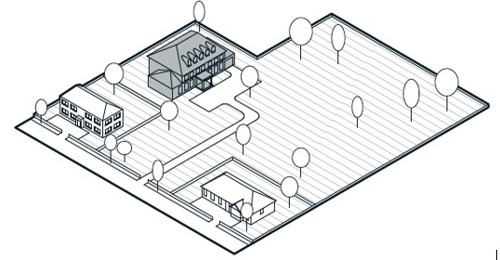

2.2 Development pattern and grain

In addition to the overall scale and visual impact of new development, applicants and their designers must demonstrate that their design solution is derived from and responds positively to the prevailing pattern and grain of development found locally.

New development proposed across the borough will need to consider how proposals respond to the prevailing pattern of development. Of particular relevance is the configuration of streets, plots, how building lines address the street, and the location of key open spaces in relation to buildings and groups of buildings.

Guidance

Building lines and the plot structure of a settlement contribute to the overall character of the area and new development must take this into consideration. Block arrangements are more likely to be found in the riverside and older parts of West Bridgford and the key settlements. Curved streets and spacious plots with large gardens are more commonly associated with the detached and semi-detached suburbs of post-war development. Irregular patterns of development can be found in the historic cores of the borough’s key settlements and in a majority of villages.

There are three main types of villages found in Rushcliffe. These are dispersed, linear and nucleated. Each have distinguishable characteristics in terms of their development pattern as a response to their location and terrain as well as economic and social functions overtime.

Another significant factor in determining local distinctiveness is the rhythm and variety of buildings and plots, or plot structure. This is referred to as grain and it derives from the size, frequency and configuration of plots. A greater frequency of smaller plots is known as fine (or tighter) grain, whereas fewer and larger plots is known as coarse (or looser) grain.

New development needs to indicate a proposed plot structure, which together with the way buildings join and relate to the street will have a substantial impact on how it responds to local character and distinctiveness.

Streets found in suburban neighbourhoods, villages and rural areas typically have greater variation in plot structure. Inner urban streets tend to have greater uniformity. For infill development in conservation areas, it is important that historic plot patterns are understood and respected.

Close attention should be given when working in or adjacent to one of the 32 different Conservation Areas in Rushcliffe. Applicants should demonstrate an understanding of the issues from the relevant Conservation Area Appraisals and Management Plans.

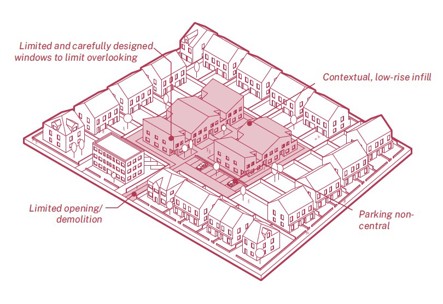

2.3 Backland developments

Backland development is considered the development of land that sits behind an established building line of existing housing or other development. This type of development often occurs in areas where principal properties have large rear gardens, such as in parts of West Bridgford, or where urban and suburban blocks have at their centre garages or outbuildings, which are usually reached via a narrow access from the public highway.

The codes relating to backland development would apply where such development is deemed acceptable when assessed against national and local planning policy. There may be sites, for example, where residential development is deemed acceptable but commercial uses would not be acceptable due to amenity issues.

C2.2

The scale and massing of new development in backland sites must not exceed that of surrounding existing buildings.

C2.3

Gates across the entrance routes into backland development will not be permitted.

- Contextual, low-rise infill

- Limited and carefully designed windows to limit overlooking

- Limited opening/ demolition

- Parking non-central

Guidance

Where the principle of development is agreed, backland development should be designed from the perspective of bringing forward benefits to adjoining residents, including increased security.

Building scale and massing must not exceed that of surrounding existing buildings. Access arrangements should be proportional to the scale of the development, appropriate to the level of use and must not over-dominate a street.

When designing backland development designers should consider how building line, connected buildings, minimal setbacks, the proportion of the building line occupied by buildings, landscaping, and the orientation of entrances and windows can be used to create a strong sense of enclosure.

It can be difficult to achieve the same level of vehicle access and parking arrangements in backland development compared to the surrounding existing development. In the riverside area type, parts of West Bridgford and the key settlements, lower parking ratios and car-free backland developments may be supported due to the high level of accessibility to the public transport network.

Gates across the entrance routes into backland development will not be permitted as a default position. Design solutions which prevent vehicle ingress, but do not inhibit pedestrian access, are acceptable, providing allowances are made for emergency and other service vehicles to access the site when necessary.

Where views into a backland development are created along new points of access, these sight-lines must be terminated by a building or key group, rather than for example, a gap or minor structure such as a garage or a side elevation.

This may not be the case in rural areas, where views into the countryside may be acceptable.

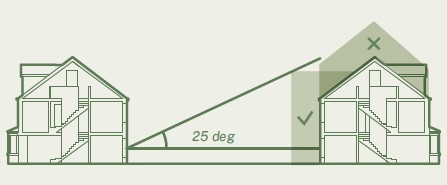

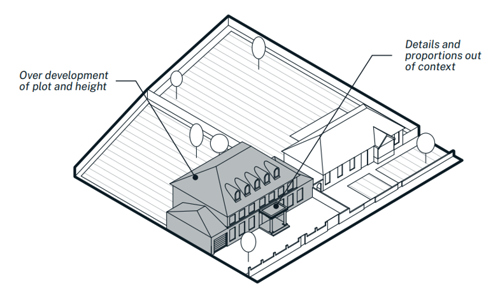

2.4 Scale of development and building height

Scale is the impression of a building when seen in relation to its surroundings. Scale can also refer to the size of parts of a building or its details, particularly as experienced in relation to the size of a person.

Sometimes it is the total dimensions of a building which give it its sense of scale, and at other times it is the size of the elements and the way they are combined. Sometimes people use the word ‘scale’ simply as a synonym for ‘size’.

This ambiguity means that when discussing the scale of a proposed development it is important that it is made clear what is meant when using the term scale.

Guidance

The impression of the overall scale of an area is influenced by prevailing local building heights, the skyline, key views and the relative prominence of local landmark buildings such as a church spire. What most people regard as the ‘right scale’ of development will fit comfortably within its surroundings. Of paramount importance is how the proposed height and massing of new development responds to the position, mass and height of the surrounding buildings.

Building heights need to consider their surroundings and ensure that they consider the significance of heritage assets and their setting, and do not dominate or diminish the asset or its setting. In all cases of infill development, but especially where new development is seeking to gently intensify local densities, design proposals must ensure access to daylight and sunlight, and safeguard the privacy and outlook for future residents and neighbouring buildings.

The urban and riverside area types have the largest scope to vary from the typical scale of the area. The urban area has a distinct scale, with streets resulting from historic patterns of development, and buildings of a consistent height and character. Along the riverside, the scale of development is generally greater, with opportunities to contrast the scale of new development. Variations in scale can contribute to the creation of attractive and memorable places by making them more legible, the creation of a strong sense of enclosure around public spaces, or through the introduction of landmarks.

In the key settlement and rural area types, the scale of development is typically consistent throughout the areas. New development that contrasts with this scale will be subject to scrutiny.

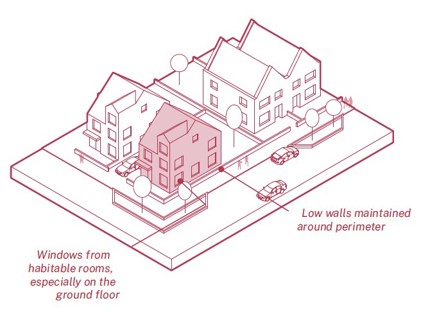

2.5 Corners

Corners plots are prominent features that require special consideration.

Buildings should respond to their double frontage with windows, entrances and openings onto both street elevations.

- Low walls maintained around perimeter

- Windows from habitable rooms, especially on the ground floor

C2.4

In new development buildings in corner plots must respond to their double frontage with no blank elevations facing a street at ground floor level.

Guidance

Street corners require special consideration. Buildings must respond to their double frontage with windows, entrances and openings onto both street elevations ensuring surveillance of the public realm and avoiding blank elevations facing the street.

Corners may be appropriate locations for taller buildings to help create legibility and identity to street networks. The increased scale should always be appropriate to its context and fully justified.

2.6 Enclosure

The enclosure of a space is influenced by the heights of features on the edge of a space, typically buildings or trees, in relation to the width of a space. Enclosure impacts how people feel when they’re within a space, affecting their sense of comfort, the types and level of activity taking place and the speed which people and vehicles move through a space.

Guidance

Streets with higher levels of enclosure are more common in the centres of settlements where streets and spaces are more people orientated. Levels of enclosure tend to weaken towards the edge of settlements where development tends to be more car orientated.

Townscape enclosure can be formed from perimeter blocks. Whether formal (orthogonal) or informal (irregular), grid structures are an efficient way of dividing space into public fronts and private backs, leading to street-focused layouts.

In the Urban Area and High Street area types, enclosure should support people-focussed streets and spaces. These contexts typically offer greater variation with street networks formed from a pattern of narrow streets and alleys, courtyards and informal squares and larger civic spaces.

Streets and buildings will be less compact as enclosure recedes in the Key Settlements and in the Rural area type. With this lower level of enclosure comes more space and opportunities for landscaping, tree planting and larger gardens.

By arranging the buildings first to form street enclosure (rather than plotting the streets first) designers have a better opportunity to respond positively to local characteristics such as street enclosure, building lines and grain.

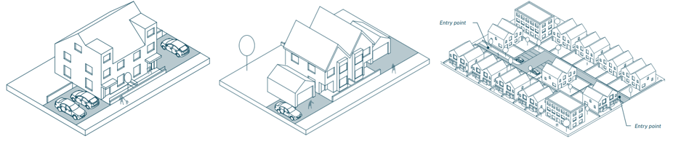

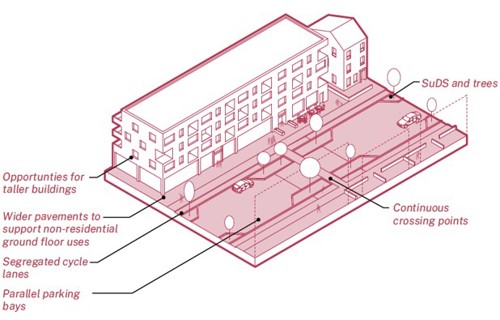

- Continuous crossing points

- Opportunities for taller buildings

- Parallel parking bays

- Segregated cycle lanes

- SuDS and trees

- Wider pavements to support non-residential ground floor uses

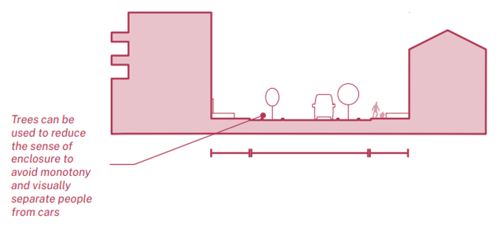

Main street in section - Trees can be used to reduce the sense of

enclosure to avoid monotony and visually separate people from cars

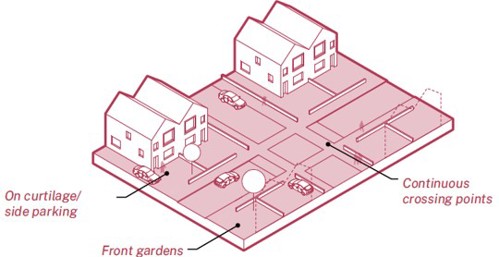

Secondary streets - should be the most common enclosure

- Continuous crossing points

- On curtilage/ side parking

Secondary street - in section

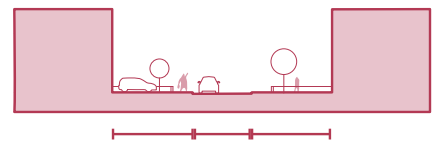

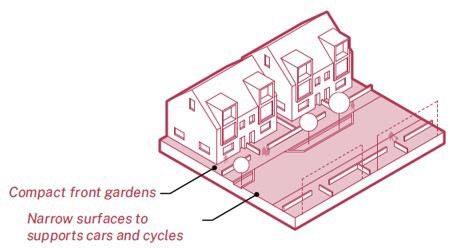

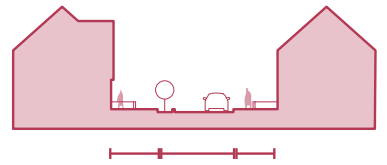

Tertiary streets - should have a tighter sense of enclosure

- Compact front gardens

- Narrow surfaces to supports cars and cycles

Tertiary streets - in section

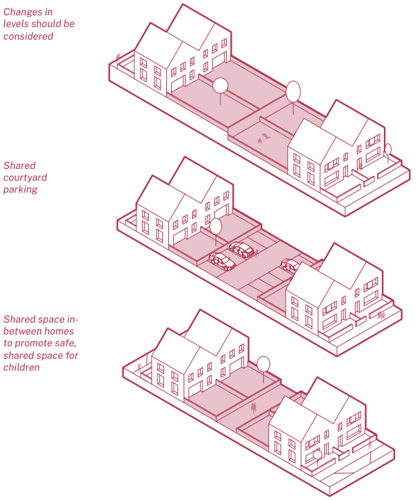

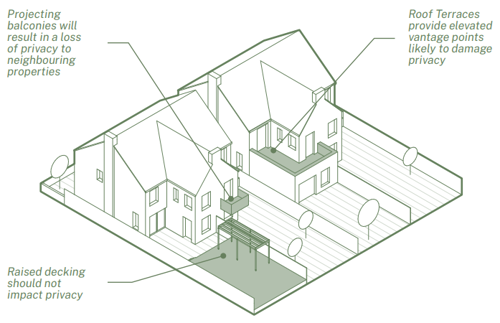

2.7 Space between homes

The distance between homes has an impact upon privacy and overlooking, loss of light and overshadowing, over-dominance and enclosure.

Guidance

Basic standards including a conventional back-to-back separation of 21 metres for two storey homes are useful reference points but are not mandatory. Strict adherence to these standards will in some instances limit design variety, unnecessarily restrict density and may not reflect local character.

Privacy

Where local context favours non-conventional distances design strategies must mitigate the impact on residents’ privacy and overshadowing. Splayed or offset façades, offset windows and landscaping could be considered.

In most cases, homes will have a more public side (front) and a more private side (rear). Where they do not, designers will need to make use of other design aspects such as internal layouts, window orientation and profile, balconies and other external elements to give residents a sense of control over the privacy of their own home. Where possible, the more private spaces of a home; bedrooms and bathrooms should be located on the more private side of the building

Plot coverage

Will vary according to location and context. In order to prevent sites being over-developed proposals should leave sufficient open space around a new dwelling for outdoor activity and access.

In detached and semi-detached family housing the proportion of plot area to building footprint should generally be greater than 60:40. In terraced housing and other more compact housing types the ratio may be much closer to 50:50 or in some cases with a higher proportion of built footprint to open space.

Private gardens

Private gardens provide important amenity space which supports well-being. Private gardens can also offer other benefits including additional biodiversity and on-site water management. To support this, all front and rear gardens must include at least 50% natural grass, planting and other forms of living vegetation. Rear gardens should be a minimum of 10 metres deep, and should meet the following minimum space standards:

- 1 - 2 bed dwellings - 55 square metres

- 3+ terraced and semi-detached dwellings - 90 square metres

- 3+ bed detached dwellings - 110 square metres

New residential proposals will be expected to meet the above guidelines whilst providing for a variety of garden sizes. Where these guidelines are not met, it should be demonstrated why smaller gardens are acceptable taking into account the overall objectives of the Design Code and planning policy requirements.

The Multi-dwellings and Taller Buildings Design Note addresses the provision of garden space for apartments.

shared courtyard parking and shared space in-between homes

to promote safe, shared pace for children

3. Multi-dwellings and Taller Buildings

When to apply this design note

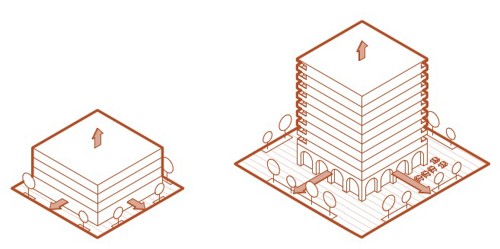

Rushcliffe has a range of scales (size of buildings) which we have defined by the areas types set out and consulted on in the baseline appraisal. We are setting out two different scales for apartment buildings which are defined as follows:

Multi-dwellings: are defined as two or more dwellings, with a shared entrance(s) and circulation. They may contain apartments across single floors, duplexes or even triplexes.

Multi-dwellings are applicable to the Riverside, Urban and Key Settlement area types.

Taller Buildings: are defined as buildings of 5 storeys and above. They can come in a variety of arrangements and will have shared entrance(s) and circulation. They may result in a significant change to the skyline of Rushcliffe and are subject to further scrutiny.

Taller buildings are applicable to the Riverside area type only.

Process

Apartment buildings can provide a range of benefits as part of new housing options in Rushcliffe.

- Allow for choice – they add to the range of new living spaces available; housing for younger generations looking for their first home, and older generations looking to downsize

- Allow for increased site density

- Common in the adaption of existing structures (offices to residential)

- Allow more people to live in central and urban locations

The baseline appraisal for the design code identified pressure to add new development, particularly residential in the Riverside area type, where there is a precedent of post-war, new-build and adapted buildings for apartment living.

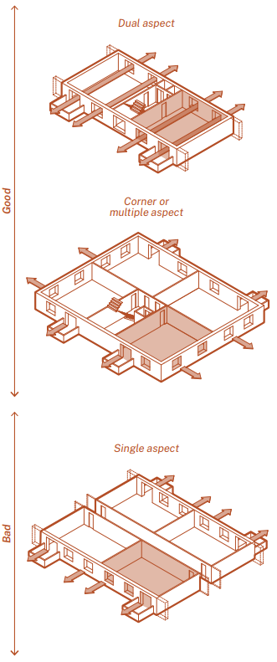

Apartment typologies refer to the common ways which residents can access their apartments within a building (for example, stairs, lifts and corridors), and the relationship between the apartments within a building. How apartments are designed can result in layouts and forms that can cause both positive and negative factors in the quality of homes.

Typologies are also not singular, they can be formed from combinations. The following section sets out the nuances of some of the key apartment typologies in relation to the following:

- Relationship between block depth (or ‘thickness’)

- Outlook from homes (or aspect)

- Private amenity

- Shared amenity

- Sociability

Differences between building typologies also determine the character of streets and spaces between the buildings. Typologies that have clearly distinguished front and rear elevations (terraced houses, dual aspect apartments) lend themselves to clearly distinguished public streets – an entrance at the front, and more private, domestic spaces to the rear.

Typologies with central corridors and cores will have frontage on all sides, creating less clearly distinguished streets and spaces between buildings and single-aspect dwellings that have only a public-facing front elevation but no rear.

There is no one singular solution, but ensuring a mix of typologies enables:

- A finer grain of urban development with more porous site edges.

- Variety in the heights, types and articulation of buildings creating intricacy in groundscape and roofscape.

- A variety of public and private streets, courtyards and spaces between buildings.

- A variety of house types to attract a range of potential future residents and enable residents to move home within a neighbourhood helping support more stable and resilient communities.

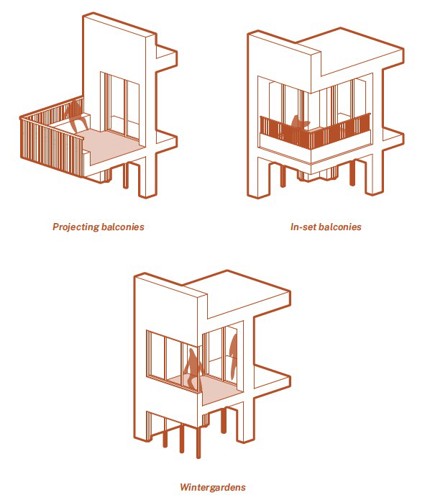

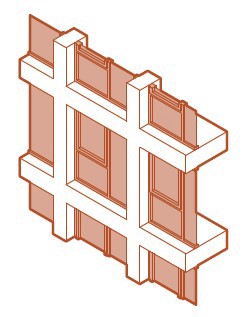

Linear Apartments

- Block Thickness: 10-12 metres

- Aspect: Dual

- (Potential) Private amenity: Front and/or back gardens, balconies, winter gardens

- (Potential) Shared amenity: Gardens / courtyards

- Potential sociability: Medium

- Street types: Clear front and back, regular entrances

Point Block

- Block Thickness: 18-25 metres

- Aspect: Single/corner

- (Potential) Private amenity: Balconies, winter gardens

- (Potential) Shared amenity: None

- Potential sociability: Low - Medium

- Street types: Frontage on all sides

Deck access - internal/ external deck access

- Block Thickness: 12-14 metres

- Aspect: Dual

- (Potential) Private amenity: Ground floor gardens, balconies, winter gardens

- (Potential) Shared amenity: Gardens/ courtyards

- Potential sociability: High

- Street types: Deck side and private side

Hybrid Example 1

- Block Thickness: 18-22 metres

- Aspect: Single/corner

- (Potential) Private amenity: Balconies, winter gardens

- (Potential) Shared amenity: None

- Potential sociability: Low - medium

- Street types: Frontage on all sides

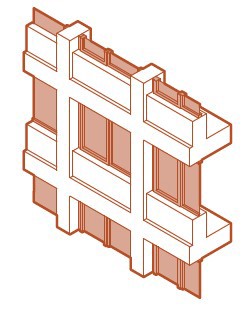

Double-loaded corridor apartment

- Block Thickness: 18-22 metres

- Aspect: Single/corner

- (Potential) Private amenity: Balconies, winter gardens

- (Potential) Shared amenity: Gardens/ courtyards

- Potential sociability : Low

- Street types: Frontage on all sides

Hybrid Example 2

- Block Thickness: 18-22 metres

- Aspect: Single/corner

- (Potential) Private amenity: Balconies, winter gardens

- (Potential) Shared amenity: None

- Potential sociability: Low - medium

- Street types: Frontage on all sides

3.1 Scale and context

Riverside

The Riverside is defined by larger and taller buildings from Trent Bridge House, the City ground, former Civic Centre (now Waterside Apartments) and County Hall amongst many. The Riverside should be the only area considered for taller buildings.

Guidance

The Riverside is a suitable place for densification given its proximity to West Bridgford and Nottingham City centre. However, it also comes with the complexities of being in flood zone 2 and 3. New development should be designed carefully to protect and support the existing heritage assets, ecology and highways infrastructure in the area.

Urban, Key settlements

The urban and key settlement area types provide opportunities for sensitive infill and intensification of plots, as well as utilising larger, but limited brownfield sites for intensification through the development of multi-dwellings.

Guidance

The urban and key settlement area types may be suitable for densification through the development of multi-dwellings. Applicants should demonstrate how apartment typologies, whether standalone or part of a suite of other housing typologies, have been developed to respond to the immediate scale and context of a site.

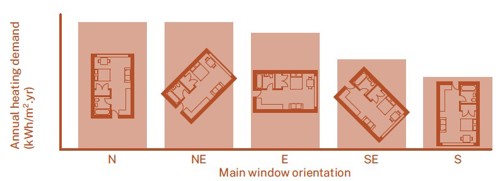

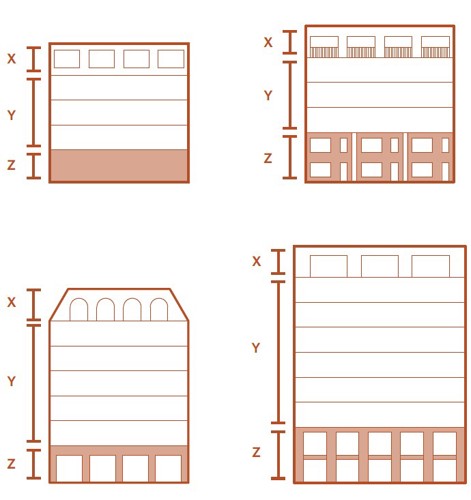

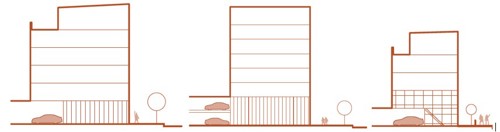

3.2 Outlook